Epistasis — the essential role of gene interactions in the structure and evolution of genetic systems

Jan 3, 2018 09:30 · 1190 words · 6 minutes read

Meta data of reading

- Journal: Nature Review Genetics

- Year: 2008

- DOI: 10.1038/nrg2452

Three meanings of epistasis

Functional epistasis

Two genes are physically interacting with each other or functionally related to each other (i.e. in the same/redundant pathways).

Compositional epistasis

It refers to the deviation from Mendelian segregation ratio. According to the pattern of the skewed ratio, the order of the two genes can be identified. Note that the order is allele-specific, namely even the gene pair kept the same, different alleles may give different orders.

Statistical epistasis

It means that the observed effect of two alleles in two genes is significantly different from the expected one (on the basis of some pre-defined models). There are two widely used models, \(W_{xy} = \alpha_x + \alpha_y + \epsilon\) (additive, simplified from dominance/recessive model, quantitative traits) and \(W_{xy} = \alpha_x \alpha_y + \epsilon\) (multiplicative, fitness).

Epistasis as a tool

It cam be used to construct gene network. High-throughput techniques has been used to survey the epistatic pairs which influence the viability of yeast (mutation was limited to deletion). Then a genetic network can be built upon such information.

Besides deletion, over-expression has also been surveyed. But it needs to be noticed again that the epistatic effect is allele-specific.

Epistasis as an obstacle

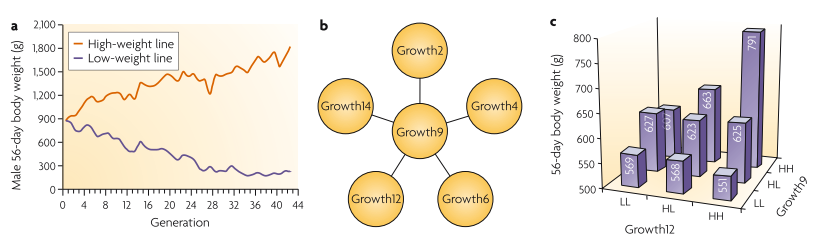

The author pointed out that the epistatic effect can cause the failure of GWAS study where only single-locus effect is considered. (Carlborg et al. 2006) provides an interesting story about how epistasis shape the phenotype under selection.

In the study, chicken were selected for different weights for 40 generations and the eQTL study was done but only one QTL was found (Growth9). However, five more additional signals were identified after considering epistasis (namly considering interaction term for each locus pair (Carlborg and Haley 2004)) as shown in the following figure.

The results of the chicken study

Comments: Interestingly, for those of QTLs that act in epistatic way with others, the conditional phenotypic variation is different (see figure c above), which is another sign of epistasis signal.

The author also mentioned that the cross-interpretation between GWAS signal and QTL-mapping is affected by epistasis if the populations are not matched for these two studies.

Epistasis in natural population

The contribution of epistasis to complex traits (beyond the additive model) is remained unknown.

Epistasis and human diseases

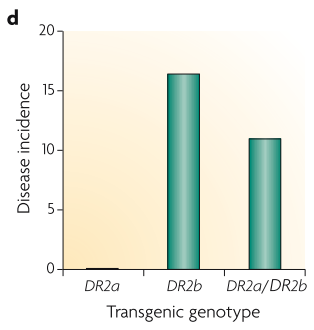

Epistasis is one explanation of why disease-causing variants still persist in populations. The paper showed an example where two loci were found to be in natural selection-induced LD in multiple sclerosis.

Testing the epistatic effect in mice

The epistatic effect was tested in mice (above figure) where one of the allele can partially rescue the effect of the other, which indicates epistasis. But in human, epistasis is hard to be tested since the underlying recombination rate between these two loci is unknown.

Inferring epistatic effect in GWAS

To limit the analysis to loci with large effect size is not valid since epistatic interaction with large effect may have relatively some marginal effect (epistasis is frequently detected in the absence of main effects).

Structure and evolution of complex systems

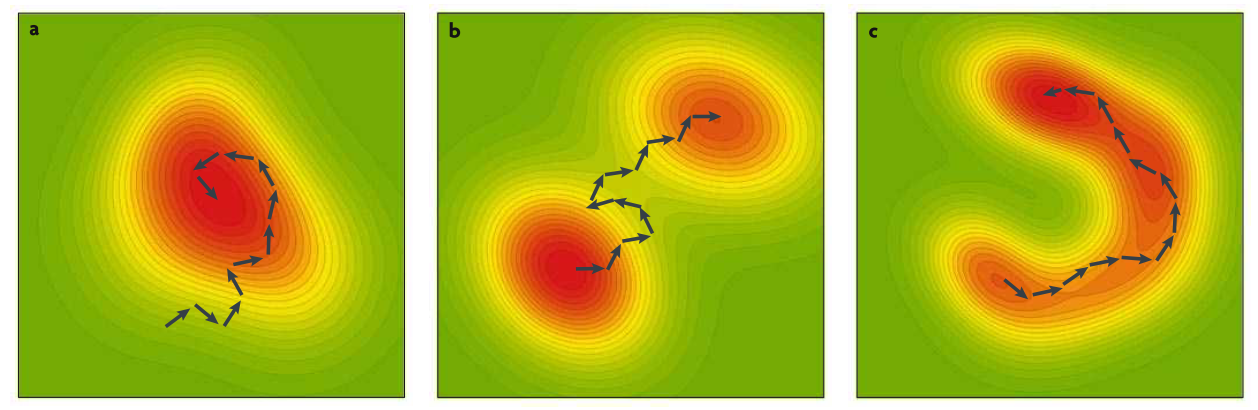

The author pointed out that epistatic effect is a natural consequence of the nature selection of complex system since every evolutionary change is built upon the previous ones. The author mentioned three views of the generation of epistasis under natural selection (figure below).

Three views of the generation of epistasis under natural selection

Fisher’s model (figure a) says that epistasis is a by-product of evolutionary process where adaption is just a hill-climbing process and the average/additive effects are the driving force. Wright’s model (figure b) says epistasis affects the direction of evolution since epistasis determines the overall fitness landscape with multiple peaks and the genetic change is due to genetic drift. Gavrelet’s model (figure c) says that since the genotype space is high-dimensional, the fitness nearly equal locally (at least for some directions) without barriers in Wright’s model, therefore the change can either by directional selection or drift.

Nevertheless, epistasis and genetic interaction are inevitable consequence of the evolutionary process.

Epistasis and the path of evolutionary change

One important question in evolutionary biology is whether epistasis determines the path of evolutionary change. The interactions between distant loci were traditional focus. The author pointed out that result obtained in the research of epistasis effect among loci in a single protein (Ortlund et al. 2007).

The evolution of regulatory complexity

It turns out that linkage can facilitate the maintenance of epistatic interactions and vice versa. It may also appear in the gene regulation in local genomic region (ENCODE paper was cited here but the result is not convincing to me, namely 5% of genomic region is under evolutionary constraint).

Conclusion

From evolutionary standpoint, one question is that whether the structure of the system has evolved to facilitate these network properties (modularity (Segre et al. 2005)).

Here the modularity means that the genes in the same module tends to have the same sign of epistatic effect on the elements outside the module. Another point of view of modularity is that the functional pathways act independently with each other, in this case, the trait is more evolvable (less pleiotropy) (Wagner, Pavlicev, and Cheverud 2007). Note that the former modularity is for single cell organism where the epistatic effect is limited within the cell. In contrast, multicellular organism may have inter-cellular epistatic effect as well.

It is necessary to unify the three meanings of epistasis as mentioned at the beginning. (Jansen 2003) gave a try to make the connection between functional epistasis and statistical epistasis.

References

Carlborg, Örjan, and Chris S Haley. 2004. “Epistasis: Too Often Neglected in Complex Trait Studies?” Nature Reviews Genetics 5 (8). Nature Publishing Group: 618–25.

Carlborg, Örjan, Lina Jacobsson, Per Åhgren, Paul Siegel, and Leif Andersson. 2006. “Epistasis and the Release of Genetic Variation During Long-Term Selection.” Nature Genetics 38 (4). Nature Publishing Group: 418–20.

Jansen, Ritsert C. 2003. “Studying Complex Biological Systems Using Multifactorial Perturbation.” Nature Reviews Genetics 4 (2). Nature Publishing Group: 145–51.

Karlin, Samuel, and Marcus W Feldman. 1978. “SIMULTANEOUS STABILITY OF D=0 AND D≠0 FOR MULTIPLICATIVE VIABILITIES AT TWO LOCI.” Genetics 90 (4): 813 LP–825. http://www.genetics.org/content/90/4/813.abstract.

Ortlund, Eric A, Jamie T Bridgham, Matthew R Redinbo, and Joseph W Thornton. 2007. “Crystal Structure of an Ancient Protein: Evolution by Conformational Epistasis.” Science 317 (5844). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1544–8.

Segre, Daniel, Alexander DeLuna, George M Church, and Roy Kishony. 2005. “Modular Epistasis in Yeast Metabolism.” Nature Genetics 37 (1). Nature Publishing Group: 77–83.

Wagner, Günter P, Mihaela Pavlicev, and James M Cheverud. 2007. “The Road to Modularity.” Nature Reviews Genetics 8 (12). Nature Publishing Group: 921–31.

Comments

The paper mentioned the issue of multiplicative model, that is LD is stable (Karlin and Feldman 1978). Therefore, a pair of genes in LD does not imply that they interact epistatically.

The difference between compositional epistasis and statistical epistasis is that the former uses a fixed genetic background but the latter uses a population where the genetic background is not identical.