Resolving the Paradox of Sex and Recombination

Jan 4, 2018 11:31 · 623 words · 3 minutes read

Meta data of reading

- Journal: Nature Review Genetics

- Year: 2002

- DOI: 10.1038/nrg761

Paradox of sex

The paradox is that despite the high cost of sex, it is extremely common.

Evolutionary explanations

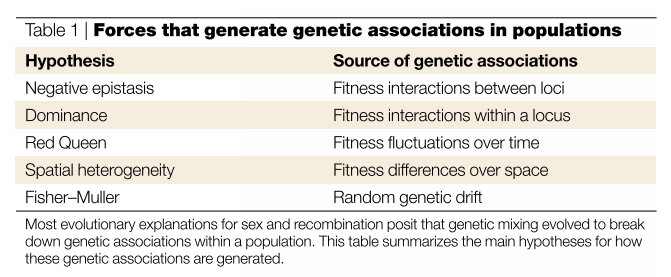

The idea of the most evolutionary hypotheses stem from the the fact that segretation and recombination break down genetic association. (The table below lists the sources of genetic association)

The forces that generate genetic associations in populations

Also, the modifier alleles is introduced to refer to the alleles that favor sex and recombination.

Terminology and Evolutionary Perspective of Sex

The linkage disequilibrium, \(D\), of two loci, A and B, is defined as the difference between the observed and expected frequency of each haplotype. In this paper, the sign of \(D\) is positive if the more extreme haplotype (AB and ab) are overrepresented.

The fraction of the sexual reproduction in the population is \(\sigma\).

The rate of effective recombination is \(\rho\).

The epistasis \(\epsilon\) is a measure of fitness interaction between alleles at different loci. In haplotype, \(\epsilon = \text{fitness}(AB) \times \text{fitness}(ab) - \text{fitness}(Ab) \times \text{fitness}(aB)\).

Effect of sec on genetic variation: Suppose \(D < 0\), the genetic mixing increase the genetic variation (by increasing the number of extreme genotypes). If \(D > 0\), the genetic mixing will decrease the genetic variation (by decreasing the number of extreme genotypes).

Variation can be selected against: Suppose heterozygote Aa is favored in the absence of sex, the sexual reproduction will generate AA and aa which are not as fit as Aa. Therefore, the genetic variation in this case is selected against.

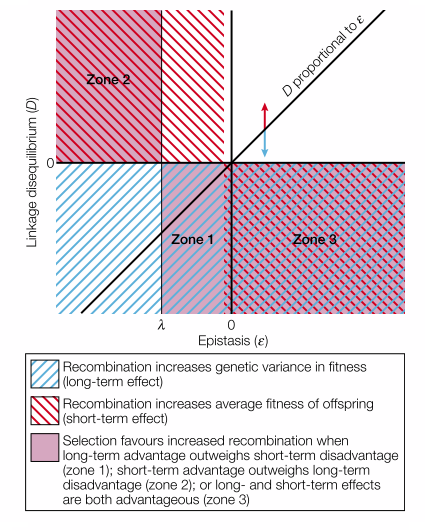

Variation alone is not sufficient: In general, variation benefits in long-term but in short term it may hurt (in other word, variation alone is not sufficient). (Barton 1995) discussed the conditions when sex and recombination are favored (namely modifier gene is spread). Suppose there is a haplotype involving gene A and B. Whenever \(D\) is negative, recombination will increase the genetic variation so that under a changing environment, it would be favored. But the spread of modifier gene depends on short-term effect as well. Since the genetic association that has been established in the current environment, the breakdown of it on average will decrease the fitness, which is known as recombination load. Combining the thought above, (Barton 1995) gives the following result:

\[\begin{align} \text{selection on modifier} &= \frac{\delta \rho}{\rho_{MAB}}D(\lambda - \epsilon) \\ \lambda &= -S_aS_b\bigg[ \frac{1}{\rho_{MA}} + \frac{1}{\rho_{MB}} - 1\bigg] \end{align}\], and the condition where modifier gene is evolutionarily favored as follow.

The conditions where selection of modifier is positive

In particular, the diagonal line corresponds to the case where linkage disequilibrium completely comes from epistasis. The red arrow corresponds to the situation where fitness of genotype is positively correlation in spatial space. T blue arrow corresponds to the situation where genetic drift exists. Therefore, in the system where epistasis is the only driving force for genetic association, sex is favored only in Zone 1 where epistasis is weak and extreme case is under-represented.

Effects of sex on segregation: The idea is similar to the recombination case when consider the genotype in diploids. The inbreeding coefficient (the discrepency to Hardy-Weinberg state), \(F\), is similar to \(D\). The single-locus interaction \(\tau\) is defined as \(\tau = \text{fitness}(AA) \times \text{fitness}(aa) - \text{fitness}(Aa)^2\). Then the similar idea follows.

Summary

From the above evolutionary model, it turns out that sex is favored as the result of epistasis, environmental difference in space, and genetic drift. Without the latter two, the condition that favors sex under the epistasis alone is very limited.

Reference

Barton, NH. 1995. “A General Model for the Evolution of Recombination.” Genetics Research 65 (2). Cambridge University Press: 123–44.